Photo Galleries

An Adventure in Chile

Potrerillos & Barquito at 13

By Frank Trask, III

On August 1, 1955 we

left Columbus, Ohio on the way to Chile.

I was well and truly off on an adventure. One of my pals in Houston was a

lad named Jim Lurie, and his father had been a junior officer on the Grace

Line before the war. Mr. Lurie had given me his old copy of The South

American Pilot, and I had the material between Panama and Chañaral

memorized! I was really ready to get out and go!

We went overnight on the Pennsylvania Railroad (First Class!) to Union

Station in New York. I was looking forward to seeing New York as a (I

thought) very mature 13-year-old. The wishing list was pretty impressive

even today. First there was the matter of seeing my beloved New York Yankees

play a home game, then I wanted to climb the stairs on the Empire State

Building, hear The New York Philharmonic, see the American Museum of Natural

History, the Planetarium, and lastly, the Statue of Liberty.

On the first afternoon, Dad and I took the subway out to Yankee Stadium, and

saw a Friday afternoon game with the Boston Red Sox. The highlight was

seeing the great Ted Williams get his 2000th major league hit. The Yankees

won handily with Whitey Ford on the mound, and Mickey Mantle collecting the

winning run. I even saw Casey Stengle have a shot at the umpire in classic

fashion. A great day for a Yankee fan.

The Empire State Building was a bit more serious. I had heard that if you

were really fit, you could get up in about one hour. I did it in 38 minutes,

and felt quite proud of myself. (The modern record for the climb is in the

order of 10 minutes) The Museum and the Planetarium were not too hard to get

to. I was turned loose with some subway tokens and given a map. We all took

in the Philharmonic and saw the then unknown (outside of New York) Leonard

Bernstein conduct a mixed program well. I did not like Mahler then or now,

but we did hear Bernstein conduct New York's own symphony, Dvorak's From the

New World. This was Mothers favorite.

Mother and Dad were shopping to get all of the supplies and goods needed to

complete a 3-year contract in a remote location in Chile. This list included

items such as a stove, refrigerator, piano, all the furniture, the lot. It

was assembled in a warehouse somewhere on the West Side of Manhattan, along

with our trunks that had been sent from Houston. All of the furniture,

appliances, and the loose material were packed in a huge packing case some 8

feet on a side.

New York was truly cosmopolitan to my eyes at that age. There were

restaurants that sold anything you could wish for, stores that sold any

record in the world, and endless bookstores. The place had vibrancy about it

that I have never experienced again in any city. This was before the

muggings became a regular feature, and one could walk the downtown sidewalks

and subways in what seemed to be complete safety.

Dad took me with him to the Anaconda office at 25 Broadway, where we met the

Mistress of Misinformation, Miss Kitty Benson. Miss Benson was supposed to

provide information to new employees to help them move to Chile. It was up

to her to answer all questions on all matters, and to arrange passage, etc.

It was instantly obvious to the most casual observer (me) that she had never

been out of New York City. I was also introduced to Vin Perry, the Chief

Geologist of Anaconda, Roy Glover, the President and a number of other

dignified looking gentlemen.

It was obvious that Dad counted for something in this office. He was

returning to the Anaconda organization after a 9-year absence. A number of

people told me later that he was always counted as an "Anaconda Man", a

wearer of the "Old Copper Collar".

Dad had left Butte and The ACMC in 1946 in disgust after the huge strikes at

the end of WWII. He had been stuck locked up inside the Stewart Mine having

to defend Company property with arms, while hooligans and cowards vented

their spleens against the company by terrorizing women and children. The

Mobs chosen form of retribution was to burn salaried employees houses out on

the flat. The Sheriff and his deputies were very distant (and disinterested)

spectators to all this. (This was and remains a good argument for not

electing law enforcement officers) My Mother had stood up to the mob with a

shotgun after spiriting my brother and I away to Deer Lodge. She got real

backup from the lad next door, a returned US Marine, who threatened the

crowd a hand grenade. Our house was thus spared from the cowards, but many

other people that were less able to defend themselves got burnt out. Dad

seemed to be getting something back from that after all of those years. He

had apparently been marked in Mr. Reno Sales "Black Book" for high promotion

when his time came, and that time seemed to be near, or at least in sight.

We had to go to the Chilean Consul's office and get our Resident visas fixed

up. There was a wonderful picture on the wall showing people with a catch of

giant rainbow trout. This served to really focus my mind on Chile as a good

place.

On August 12, 1955 we set sail on the USS Santa Margarita of the Grace Line.

The Margarita was a twin to the Luisa and Maria that we had taken to Ecuador

in 1946 and 1949. We sailed from Pier 57, and had Cabin 1, the forward

premier cabin on the A deck, starboard side. These ships carried 52

passengers, and rated a doctor on board. Most of the passengers were going

to South America to work, but there were a few retired types. On the way

down the harbor I finally got my look at the Statue of Liberty.

A “Santa” 52 Class Combo ship, underway, probably the USS Santa Luisa, photo courtesy of George Gillow

The voyage started out all wrong. We sailed at 1PM, and by 4 PM I was

convinced that the Captain was crazy. The setting sun was directly off our

stern. I ran up to the top observation deck, immediately above the bridge,

where the spare compass was shipped. This seemed to confirm that we were

headed toward Le Havre at best. I struck up a conversation with the Radio

Operator, who informed me that we were steaming (oiling to be proper) as far

to the east as practicable to get around a massive hurricane that was

working its way up the Atlantic coast. As soon as we were far enough east of

the projected center of the storm, we would turn and bear south. This would

put the ship bow on into the worst of the wind and seas, and restrict the

side rolling of the ship. By the time the sun had set, we were obviously in

for a raging night. At dinner Captain Berg announced that the decks were

closed excepting the rear A Deck. This looked directly over the swimming

pool and was protected on all sides. A trip back there revealed some truly

impressive seas that were washing over the lower deck, with some of them

slopping up to the level of the A Deck. A quick way to fill the swimming

pool! I went to bed every inch of me a blooded mariner.

Morning revealed a wild scene. The waves had grown in amplitude to the point

where you were looking up from the cabin at the oncoming seas before they

struck the bow. The wave would then break over the fore deck and crash

against the house. As the cabin windows formed the front of the house on A

Deck we got to see a lot of water. I later found out that we had passed

within 50 nautical miles of the eye of the hurricane.

The day after the hurricane passed, we came on deck to glorious weather. We

were just entering the Windward Passage between Cuba and Dominica. When I

had previously made this trip, this passage of water had stirred up all

sorts of ideas about the old pirates on the Spanish Main. I was much more

interested in the workings of the motor ship this time, and had by then

formed a good friendship with most of the crew. The inner works of the ship

were out of bounds to the passengers excepting one tour of the engine room,

for men only. I had already worked my way into the radio operator's room,

and was busily occupied there "helping". The man had a new radio telex

machine, and he made it my duty to feed the thing with sheets of paper when

the morning messages came in. This soon led to an introduction to the Chief

Engineer and access to the engine room. Here I had an intimate look at the

machinery of the ship, and made a great discovery. There was a brand new

Chevrolet Suburban Wagon in the forward hold, and it was addressed to Dad,

at Chañaral, Chile. I asked him casually if he had bought a new car while we

were in New York, but he denied this. He immediately demanded to know why I

was asking the question so I told him. The car belonged to Andes Copper but

our family had a right, as paid First Class passengers, to transport one

motor car for free to our port of destination. It did, in time; end up in

the Geology Department.

It was 5 days to the Panama Canal from New York, and the passage of the

canal was a carbon copy of what I could remember from 1949 on the Santa

Maria.

After passing through the canal we were on our way down the West Coast of

South America. My Dad picked up just at the thought of it. Our next stop was

Buenaventura, in Columbia. The sole occupation of this town seemed to be to

rot the husk off of coffee beans. These were spread out in great piles on

the wharf, and alternately allowed to rot, and then dry. The smell was

amazing. The ship unloaded a bit of machinery and other goods, and proceeded

to spend two days loading sacks of coffee beans by hand.

SS Santa Rosita, the Grace Line Launch stationed at Guayaquil (Photo courtesy George Gillow)

We were happy to leave Buenaventura behind and get on to Puna. This was our

old homeport, and I yearned for the chance to take the Santa Rosita up the

river to Guyaquil. Alas, it was to be a one way trip only. We sat at anchor

for about 18 hours. A huge human chain of stevedores carried an endless

supply of green banana stalks up very shaky planks from lighters and into

the refrigerated hold. The Rio Guayas was still the same, stinky and muddy.

The next stop was Talara, which was only just south of the Ecuadorian

border, but obviously the start of something new to me. The jungle was gone

and replaced by a desert. The salt water in the pool was cold, all within 5o

of the equator. The famous cold Humboldt Current causes this.

Callao, the port for Lima, Peru was next. It was notable by meeting Carlos

Plenge. He had attended the Montana School of Mines with Dad, taking a

Masters Degree in Metallurgy in 1935-37. He had us for lunch to celebrate

Dad's birthday on August 21, his 42nd birthday. Afterwards we all went to

the bar of the Hotel Bolivar and met with Allen Engelhart and his wife. Al

was the General Manager at Cerro de Pasco, and like Dad and Carlos, a

Montana School of Mines man. He had been the Manager at Portovelo in Ecuador

where we had lived between 1946 and 1951. As we left we met Bill Honeywell,

a mining engineer type that had worked at Portovelo as well. He was working

as a mining machinery salesman out of Lima, and seemed to make his living

drinking booze.

Rudyard Kipling wrote about the emotions of Anglo-Indians returning to

India, and what we felt about West Coast South America was just like that.

"Here was the land we knew and loved, before us lay the good life that we

understood, among people of our own caste and mind." The next stops

were at Mollendo, Illo, Arica, and Antofagasta. The ship stayed here for

three days while a huge tonnage of copper was loaded from the mine at

Chuiquicamata.

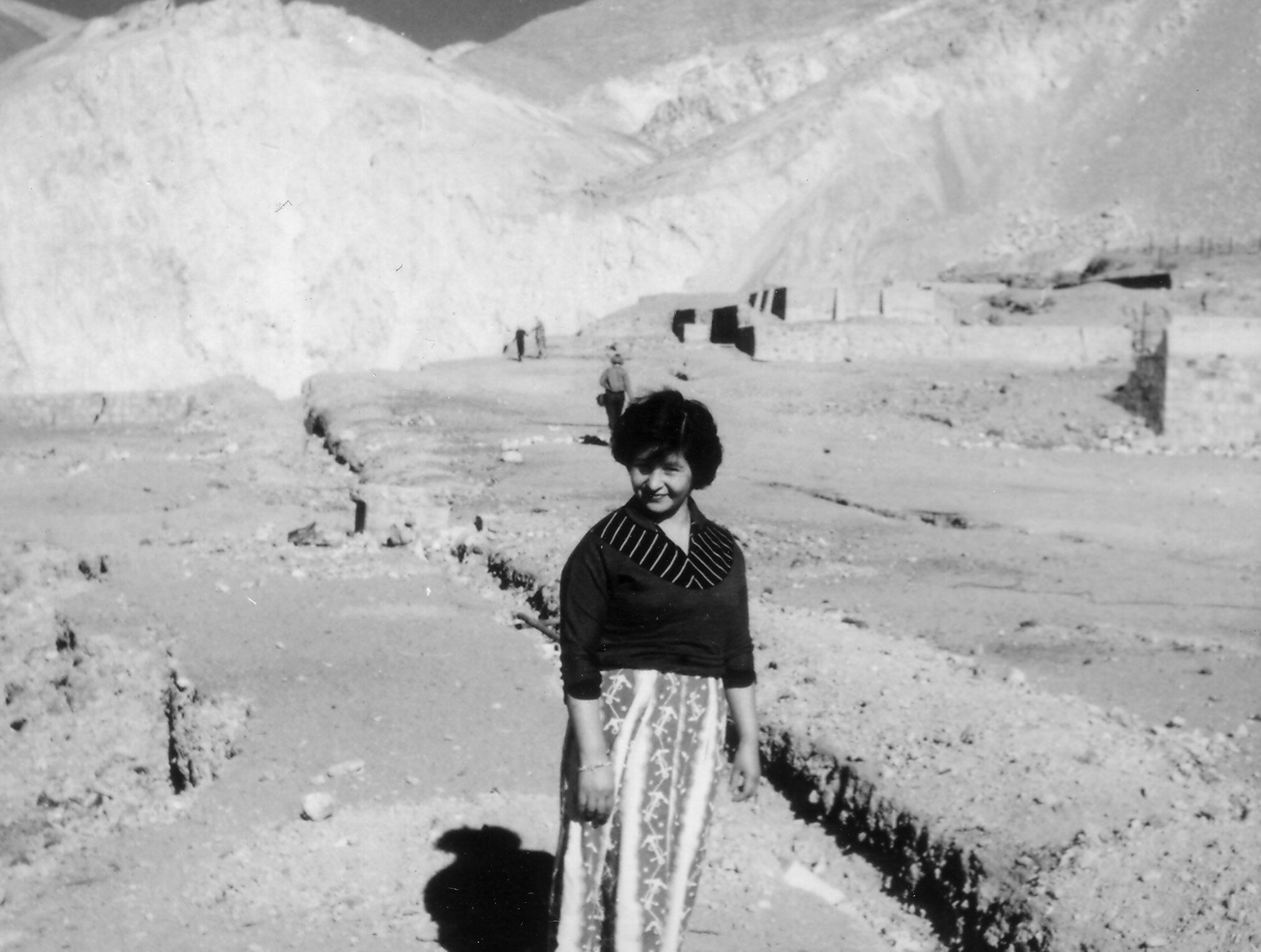

The next afternoon, Thursday September 1, 1955, we arrived at Barquito, our

Port of Call. This appeared as a small settlement that was pasted on to some

granite rocks about 1 mile west of the port of Chañaral. The picture below

shows my Mother contemplating her future home.

Anne Blake Trask (1915-1957) contemplating Barquito on September 1, 1955

There were a number of large oil tanks, a power station and a small dock.

The Grace Line tug came alongside, and it immediately showed that we were

back in the hands of The Anaconda Company. Its name was Colusa, obviously

(to someone from Butte) named after the famous mine at Butte. The great

point of interest now was getting off the ship. Hurried good-byes were made

to the people that we had met, tips provided to the waiters and the like,

and over we went. A very narrow gangway had been lowered. There was a

tremendous swell, (which was not usual) and the obvious difference in weight

between the tug (The Potrerillos) and the large ship caused them to rise and

fall with very different motions and times. This was pretty tricky. You had

to grab a rope, wait for the two vessels to coincide and leap. If you caught

it on an upstroke, you got a nasty hit when you hit the other deck, and on a

down stroke you could take a fall of 6 or 8 feet, enough to really hurt you.

Dad and I did it OK, but Mother had a hard time of it. This came as a real

shock to me. Not 5 years before she could step off the back off a horse at a

good speed and land on her feet running. Dad eventually got her into his

hands and simply lifted her on to the tug.

Mother had major surgery for thyroid cancer in 1952, followed by a heap of

radiotherapy. I found out many years later from my Grandmother that Mother

knew the cancer was back when we left for Chile, but had told no one but

her. She also had to take a lot of medication to replace her thyroid gland,

and the pills had a terrible effect on her balance, both physically and

mentally. It was not a good situation. She was, however, very happy to be

back in South America where my Dad was happy.

The next test was to get off the tug and onto the wharf itself. This was

done by grabbing a rope and swinging a la Tarzan down on to the platform.

Great when you are 13. The crew had a special platform that they rigged for

Mother, and she went over like a lady. Mr. Peake met us and informed us that

a number of our trunks had fallen from a cargo net, and were on the bottom.

It would be a month before a Navy Diver was due through, but "not to worry,

we always get them back". It turned out to be only two of the trunks. One

was full of Dads books, which were inside rubber sealed ammunition cases.

They came out as dry as toast, and I have many of them today. The other had

the silverware and the phonograph records in it. The silverware sits on my

table today, but the record collection was ruined.

Barquito was the terminus of the Ferroc. de Potrerillos, and was the port of

the Andes Copper Mining Company. For people from Montana, it was obvious

that the initials of this mining operation were the same as those at Butte.

(I often wondered why some acronymophiliac had not named the railroad the

Barquito, Andes and Potrerillos, to follow the Butte, Anaconda and Pacific

at Butte!) The actual trip to Potrerillos (10,000 feet high) was made in a

1946 GMC Suburban Autocar.

F De P Track Cars, (Photo courtesy of George Gillow and www.LosAndinos.com)

The trip to this quite forbidding looking mining camp was only 150

kilometers in a straight line, but about 200 on the railroad. This trip took

most of 5 hours, which is pretty slow by any standard.

We spent the afternoon walking over to Chañaral,

filling in custom forms, and generally looking around the place. We met with

the urbane and charming Customs Inspector, Don Norberto Rojas. He was later

to become a good friend and fishing companion. I remember gray clouds and

cold weather today. The guesthouse was furnished as all guesthouses are with

thin blankets and thick crockery, all listed out on a mimeographed sheet

with many alterations in many different hands! We went to dinner at the

Rancho where we got a very pleasant surprise. The fresh Congrio was

absolutely first rate, as was the very cheap red wine.

The trip on the autocarril started at 12:30 and culminated with arrival at

the Potrerillos rail station at 5PM. After you left Chanaral, the rail went

past the outcrop of a large granite batholith. This hillside on the left

with its prominent basic dikes is one of the great outcrops for a geologist

to see in his lifetime. My first photo taken in Chile is still with us, and

included here.

Vertical basic dikes in the Permian Chañaral Granite batholith, east of Chañaral.

The rail went up the tailings creek (the Rio Sal) past Salado, Pueblo

Hundido, (where we waited for the down train full of copper to clear the

track) on to Llanta, the F de P rail headquarters, and thence up a narrow

valley that rapidly became a deep canyon. The mine had to be up there

somewhere, because the tailings stream and the power line were both right

beside the track all the way. After about 4 hours, the walls of the canyon

rose to over 3000 feet above the bottom and the grade of the rail became so

steep that the railcar was in low gear. The ever-present tailings then

disappeared up a steep gorge to the right, as did the power line. These were

good clues that we must be getting close. At this point the rail left the

bottom, and started up a cut that eventually led to Potrerillos. The

alarming bit came on the steep curves that were cut into the walls. The

brakes on the machine were operated by the steering wheel. Going around a

left-hand bend while the driver frantically turned the wheel to the right

was a bit unnerving.

We arrived at Potrerillos late in the afternoon of September 2, 1955. It was

a good mining camp, and was run by some of the nicest people that I have

ever known. Ed Brinley met us, and escorted us to a comfortable house on the

lower southwest side of D Row. The Bates lived on the uphill side, and the

Dudley's downhill.

I was entered into the last half of Grade 7. The teacher was Mrs. Nona

Marsh, and she looked at my name and asked if we came from Deer Lodge. When

this was confirmed, she said to “ Tell your Father that Miss Sackett is

here”. She had taught at Powell County High when he was there. She had just

gotten her chance to terrorize the second generation of a family! She was a

tough teacher, but she also got results. We were also required to take part

of our schooling in formal Spanish. My classmates in the 7th grade were

Billy Bennett and Pat Daspit. I think that Joan Novak and Judy Vetersneck

were in Grade 8. As with all kids, you almost never really remember the

younger ones.

My first impression of Potrerillos is one that still is with me, 49 years

later as I write these words. (Luck finds me writing this on September 1,

2004, 49 years to the day that we arrived in Chile. I am whiling away an

evening in the office of a small mine at Cloncurry, Queensland, a place

almost as desolate as Potrerillos, but without the saving grace of scenery).

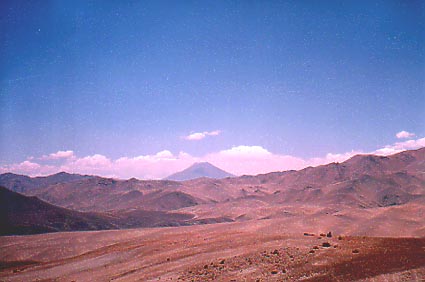

The topography was stupendous, almost magical. The wonderful and graceful

outlines of Cerro Vicuna to the SW, with its arcuate and cockscomb ridge

trailing to the north, and serving as a left frame for the sunset is the

first feature. Vicuna was easily seen from the Margarita before Chanaral was

sighted, and was the constant visual contact during the whole of the rail

car trip. The modernistic clash between the nearly flat pediment of tertiary

sediment and the hills to the NW made the other side of the frame for the

sunset. To the west was a vista as long as a man could see over the

curvature of the earth. I learned spherical trigonometry trying to prove

that you could see the ocean from the bottom of D row! (In theory you

could.) Then to the NE, rising like a magical mountain out of the foothills

that were spread around in a chaotic pattern rose the form of Dona Inez,

with a coat of snow. Purple streaks peeked out through the white, which

shone like silver, and then in alpine sunset gold, to show the angular form

of this most graceful volcano. The only thing missing was a plume of smoke.

The alpen gluehen in the late sunset was the greatest in the world.

Cerro Doña Inez, view from Hospital, Potrerillos, Chile. (Courtesy of www.LosAndinos.com)

I initially started out being quite friendly with Billy Bennett. Bill had a

light motorbike, and would roar around the curve in front of the house in

fine style. Bill's Dad was the General Manager, but was certainly

subordinate to Mr. Koepel who lived in the Gerencia over the way from them.

Potrerillos must have been the only mining camp in South America where the

Manager did not live on the top of the hill. Bill and I did quite a bit of

poking around the gulches below the limestone mine and found quite a deposit

of agates in the volcanic agglomerates at the bottom of the gulch

immediately below the Gerencia. Mrs Bennett was very interested in these

agates, and surprised me by climbing down to and back up again from this

place with the greatest of ease. My Mother cut quite a few nice cabochons

out of these small-banded agates.

Billy was very much the Manager's son, spoiled and very confident of his

position in the scheme of things. He was also contemptuous of his Fathers

superiors and inferiors to the other kids, which my instincts led me to

believe was not a healthy thing! Our friendship sort of ended about as soon

as it was started.

Our first family expedition out of Potrerillos was to go to Indio Muerto.

Bill Swayne picked up Mother, Dad and, myself early on the morning of

September 18 in his Dodge Power Wagon. We drove to the small camp at Indio

Muerto, arriving by 9AM. Dad and Bill spent the whole day clambering all

over the mountain looking at drill sites and outcrops of what had been

proven to be the leached cap of a copper deposit. Exactly how big a deposit

remained to be proven, and this was Dad’s major job over the next 6 months

or so.

Mother and I spent the day mining a large amount of gem and near gem quality

turquoise from the old Inca (Coya) mines. These were simple “dog holes” that

had been dug with very rudimentary wood and stone tools. Proper work with

“modern” picks and shovels certainly brought out a lot of turquoise. It was

very pale compared to the stuff sold in gem shops. I have a surviving piece

from this trip and did an X-Ray Diffraction test on it in 2001. It is indeed

really turquoise, and by boiling it in olive oil, one can get a superb

color, just like the ones in the gem shops. Too bad we did not know about

this in 1955.

Mother had purchased a gem polishing and faceting machine in New York, and

she used this to really good effect. She produced a huge number of cabochon

stones over the next two weeks. Many of these were given away to various

people, and some were set into jewelry, but by whom I do not know.

Over the weekend that included the holiday Todos Santos (Or San Pedro y

Pablo, November 1) we made a trip to La Ola to try the trout fishing. All my

trout fishing had been with flies, and this did not work here. You could see

the damn fish and they would not rise at a thing. Dad soon pointed out that

perhaps since there were no mosquitos, there were no insects at all. I tried

a small spoon and got instant recognition from at least one fish. It turned

out to be a slow day, but I ended with three beautiful fish in the 15 inch

class. They were top eating. The trip was almost magical, getting up on to

the real altiplano, right at the feet of the volcanoes. I felt cheated that

none of them were active!

One of the more humorous events that we experienced (it was funny to some of

the family) happened in the first week. Dad owned a fine old Harris Tweed

coat that he had purchased as a student in 1936. This coat had sort of

gotten into the public monument category, leather elbows and the like, and

was much loved but worse for wear. Mother had made a few attempts to dispose

of it over the years, and she thought that she had at last succeeded. She

had put it into the garbage can when we were packing up in the States. When

she was emptying the last of the trunks, the one with the guns, tools and

fishing bits, here it was, carefully put away. Pop had obviously spotted it

and gotten it into the one trunk that he could pack without fear of

supervision. Just at the moment of discovery, there was a knock on the door.

It was a fairly ragged and coal dusted man whose duty it was to stoke the

furnace every evening. He was very pleasant and courteous to Mother who

formed an immediate and lasting friendship by making a present of the prized

Harris Tweed. She nicknamed him Don Sucio, Sir Filthy. A few nights later

Dad commented that he had seen the “Coal Man” wearing a “really good looking

tweed coat”. He said he would have to speak to him and find out where he got

it!

I soon became very good friends with Charles Bates who lived next door. We

got into climbing, and got on top of all the local peaks on weekends. The

picture below is of Chuck on top of the Smelter Hill, October 16, 1955.

Charles (Chuck) Bates, a fearless mountaineer and my chum. Smelter Hill, Potrerillos Chile, October 16, 1955

This got me up to around 14,500 feet, higher than any point in the main USA.

I also got my start in the lime industry by meeting Pappy Johns and hanging

around the limestone quarry and the limekiln. Potrerillos was a wonderful

camp for a boy of my age. The social life was very different to that I had

experienced in the USA. The girls were all into dancing and being a lot more

grown up. Like children everywhere they imitated their parents, and when

they had social functions they tended to be formal with proper dress.

Dad was absolutely happy in his new position. I will never forget his

absolute joy when he came home from one of his first management meetings.

This was one of Mr. Koepel's famous "confession" sessions. Dad's delight was

that the company was not only staffed with nice people that were competent,

but that the upper management was modern and top class. He soon came to the

opinion that Mr. Koepel was one of the original nice and competent people. I

have recently ( March, 2005) recovered all of my Mothers letters that she

wrote home during this time. She wrote that” Frank feels that his career is

made, a top position with pleasant people and a chance to do the greatest

and most complex geology job in the world” She was certainly right!

One of the most pleasant surprises came a few nights after our arrival when

the Mine Superintendent, John Hoffman, asked us to dinner. It turned out

that Ole Olsen who had been the Mine Accountant where we had lived in

Ecuador was Oulgita Hoffman’s father. We had known her sister Nancy and

brother Edgar when they came to Ecuador to visit for several months in 1950.

When we knocked on the door there was Nancy to surprise us! This renewing of

a very old and valuable family friendship really set the tone for our

familles love of Potrerillos. Sadly, Ole was not well, and died before we

could get to Santiago to see him again.

Gene Wheeler (Who worked for Dad in the Geology Department) had started a

Boy Scout Troop of sorts. Along with a lot of other activities, he proposed

a fishing trip to Pan de Azucar. This was the most popular idea that he had

come up with. The whole outfit went to Barquito on a mid afternoon on Friday

(in spite of protestations about Monday's composition from Mrs. Marsh) in a

special track car, and camped in one of the upper row houses at Barquito.

The party was joined by Messers. Koepel, Bennett, and Libenow the next

morning, and all headed for Pan de Azucar. The adults certainly knew what

they were doing, and were equipped with the latest spinning gear. The

Trask's were hicks from Montana, and I had some fly-fishing gear and one

hand line, all obviously unsuited for catching the magnificent linguados, or

flounder. And the fish were really biting!

Instead of bitching about not having the right gear like the other kids, I

got one of Mr. Koepel's gaffs in my hand and made myself useful helping the

adults to get some fish up on to the rocks. I had an admiration for this

man, then and now. He was the real thing, a strong and powerful leader that

demanded absolute respect, and gave a lot of warm affection back. He soon

saw that I was interested in fishing and really did want to catch one of the

linguados. He stopped everything, showed me how to rig up my hand line, and

how to cast it. When I caught a really nice fish on the first try, he helped

me land it, and took my picture. He also gave me a little homily about the

value of respect for your betters and hard work, and declared that he was my

friend.

Dad was asked to go to Bolivia to look at a natural gas field. This meant that he was to be away over both Christmas and New Years. Potrerillos was a dismal place for Christmas as far as Mama was concerned. She had a magnificent set of old German hand blown glass ornaments for a Christmas tree, and it was her annual pride to put these to use on a proper Christmas tree. It was unimaginable to her that there was not one for sale. At Portovelo, the company provided you with a live tree in a tub that was kept at the Company Garden for most of the year. Even Bonanza, in Nicaragua, which was in the snake infested Central American Rainforest could muster a decent Christmas tree. As Christmas got closer, she became pretty inquisitive. Finally Mr. Libenow informed her that no one had ever ordered or gotten a Christmas tree in his knowledge. Mama was not very easily defeated. She went around to See Mrs. Fines, who has several Pencil Pines in her garden. With MariLu’s help, the two of them raided as many branches as could be cut off the various cedar trees around the place. Mama assembled them into a magnificent Christmas tree that was admired by all who saw it.

I became ill on Christmas Eve and was sent to the hospital with suspected

appendicitis. This turned out to be a false alarm. On New Years Day I was

home alone with Mother when she suffered a massive stroke at 3:30 AM. The

head Doctor did not respond to my call for help at 4AM. (He told me she had

a hangover, a very poor telephone diagnosis, and almost certainly a critical

mistake in the path that lead to my Mothers very young death a year later.)

I finally got Bess Barnes from the hospital to pay some attention, and

Mother was taken to hospital around 8 in the morning. She was packed up and

sent to the company hospital in Barquito within the hour. This was a

sensible way to lower blood pressure. Since it was school vacation, I was

sent along a week later to help look after her. Barquito was where many

people would take a week or two off to escape from the altitude. I spent the

next two months more or less on my own in a fairly immoral Latin American

seaport. Just the place to be when you are 13 going on 14! Iwas placed

in one of the lower duplex houses, over the road from the Rancho, and lived

on my own, going to the hospital and trying to keep Mother company. She was

sick, partly paralyzed, and distracted and did not really want anyone to see

her unless she was having a good day.

Roger Forget and his two children, Duplex Barquito, January 10, 1956

Dad arranged people to look after me as best he could. The first week I had

my meals with Roger Forget and his family, the next week, I lost the house,

or rather, shared it with Kathy and Ernie Lucero. The week after that I ate

lunch with the Dunstan's, the week after that with the Hoffman's, etc. I got

to know a lot of fine people, who were very kind to me. I also got to know

my way around Chañaral in a way that might not have been too acceptable.

I knew where and how to get anything. (I must have been something like

Kipling’s Kim, the “Friend of all the world”) I surprised Kathy Lucero who

was trying to purchase three crates of beer. There was a shipping strike on,

and there was no beer. Kathy and Ernie had a certain style about their lives

to uphold, and a crate or so of beer was needed to make the holiday a

success. They got Mr. Peake to drive them over to Chañaral and tried all the

usual places with no luck. The town was dry. I told Kathy the next day I

knew a place where they could buy all the beer they wanted, and led her into

the parlor of the local brothel! She was fairly scandalized. They did get

the beer! (I must admit that I did not really know what went on in there!)

I became a regular on the Potrerillos, the Andes tug, and the Barquito, a

small workboat that also had a bowsprit on it in order to harpoon swordfish

in the right season. The Potrerillos can be seen on the left, and Barquito

immediately below the right elbow of the rear man.

Boat Crew, Barquito, Chile January 1956 (Gaston is in front)

These boat crews were really nice guys, and interested in fishing. I became

a very good friends with one Gaston who showed me the ropes when it came to

local fishing. I believe that his last name was Giepert, but I am not

positive. Inshore fishing off the rocks was pretty slow, but not impossible

as the photo below shows.

Frank Trask, III (Me), Barquito Chile, January, 1956

There was a fairly good catch of peccireys on most days. These were a small

smelt like fish that could be crisp fried and eaten whole. The doctor that

was treating Mother loved them, and it was my pleasure to bring all I could

catch to the Rancho where it was served as an entrée. The commercial

fishermen over at Chanaral were the real tough guys. They went outside most

nights, and during one phase of the moon (I forget which one now, but I

think they got them in the moonlight) they brought back masses of congrio,

or what are called conger eels in New Zealand and England. These were

excellent eating, and as long as there were lots of Gringo's down at

Barquito, I could always earn an easy lunch and a bit of gratitude by

fetching fresh congrios from the open market. You could even scalp a bit of

a profit out of the hostess! Dad wrote home to my Grandmother, “Frank is

running wild getting in all of the fishing that anyone could imagine. He

caught 35 fish yesterday, one of them a good 31 inches, as the photo shows.

He gives them to the people here, and then sponges a free dinner from them!”

He also noted that “ Mrs. Bennett, the Managers wife, is very kind to Anne,

and visits her 2-3 times a day, brining her special treats so she will eat

properly.”

I made a forbidden (or rather secret) overnight trip off shore with one of

the deep-sea fishing boats, and had the time of my life helping them pull in

the fish on long lines.

Of all the things that I remember from that two months in Barquito, what is

overriding today is the people. The Trask's were in reality strangers to

Potrerillos, but we became "family" to everyone. The real love and

friendship shown to me by these various people is to me what Potrerillos was

all about. It was certainly all for one and one for all when it came to

belonging to the Potrerillos community! I will list a number of scenes that

sit in my mind about people and places.

Eating lunch with Henry, Peg and John Dunstan every day for a week. I had

never seen an Englishman handle a knife and fork that way before and was

fascinated. Instead of being insulted, they taught me to eat that way. It

scandalized my Mother!

The smell of cedar trees in the hedge by the gerencia on a warn night.

Mrs. Marsh came down for a week, and held court for all of the school age

kids. We went to her place for Scrabble and Bidu (A horrible Coca-Cola

imitation) every night. The Scrabble competition turned into a pretty good

school session.

I learned how to hold hands and giggle in the dark with a young lady named

Marla Grey. We left our initials scratched in the plaster under the porch of

the duplex next to the hospital. They might still be there!

The Doctors and nurses in the hospital that looked after Mother. Not only

did they do this well, but also they looked after me. They taught me to play

Canasta in the evenings, and I skinned them all at it after a few weeks. I

cannot remember their names, but one of the nurses later went to Potrerillos

and (I think it was she) married Sergio Chaves. They were great fun, and

their obvious concern and competency rested my mind about Mother.

Listening to Slim Welch tell of his home in Alabama, and about how the gold

watch he was given for 25 service to Andes turned green every summer.

Sneaking a ride to Pueblo Hundido on the "Up" train in the morning, and

making it back to Barquito for late afternoon on the "Down" train. The train

crews were great guys and good friends.

My birthday present that year was a return to Potrerillos on March 8, 1956.

By this time Mother was starting to recover, and was able to get out and

walk around the place. She was put into one of the duplex houses (C5) on the

lower row, just above the police station. A maid was hired from Chanaral,

and Mother seemed to be on the mend. Dad took me back to Potrerillos, and to

what seemed like prison life, homework and schedules. I could not even

remember what side of a column of numbers to start to add from.

Dad and I drove down to Barquito on Friday nights and returned late on

Sunday afternoon. Andes was always very strict about people checking in by

phone when they left Barquito, calling again from Pueblo Hundido, and then

checking in at the gate. Mr. Koepel would personally stay up if a car was

overdue. We always stopped and checked in with Kep before we went to the

house.

We often got a ride from Mr. Bennett or others that might have been going

down for a weekend, and this meant that there was a new truck or automobile

that needed to be driven “up the hill”. Once we got a brand new Chevrolet

Sedan that went directly to Harold Robbins. The next weekend we were to pick

up another one, and I thought that this was going to be OK. It turned out to

be a new van for the Pulperia, and a real dog. It turned the usual 2-hour

trip into 4 hours, with the entire hill climb being done in compound gear.

There was no passenger seat, and I did the trip standing and hanging on to a

pole in the back.

We also got anyone that wanted to come back and forth as passengers`. There

was one trip where we had an attack of the “flats”, with both spares being

punctured before we got to Pueblo Hundido. We got them fixed there, and

called ahead to Potrerillos. We had another flat by the Inca del Oro turn

off, and the next one at El Jardin. One of the passengers was Breese Rosset,

a famous and crusty mining salesman noted for his hard drinking and

gambling. He was no athlete, as he chose to sit in the car and wait. Pop and

I walked up the hill in the moonlight. We were about 100 meters from the

gates when Blaine Wiseman pulled up with 4 new mounted spares. It was nice

night for a walk, but very cold. On another trip, the steering rod on the

Geology Department “Green Dragon” or GMC Suburban wagon snapped off. This

happened just as we got over the grade coming up to the Inca Del Oro

turnoff. If it has happened 100 meters earlier, we would have been over the

side of the Quebrada. Both of these instances showed the wisdom of having

people check in when they came and went.

The house was a mess with Dad working hard and not having any domestic help.

He had tried many times to hire a maid, but none came forth. We ate at the

Rancho, so at least the Kitchen was clean!

Josefina and Harold Robbins asked Dad and I over for dinner, and Dad briefly

mentioned to her that we needed to hire some help, because Mother was coming

home in 2 weeks. We went to Barquito on the Friday night as usual. There was

a message waiting from Josefina that she had hired a maid for us, and that

she would be in the house when we got back. I have no idea to this day what

Josefina or for that matter maybe many other ladies of the camp did that

weekend, but on Sunday night the house was immaculate.

Her name was Raquel, and she was magic. Raquel became a companion and friend

of my Mother as well as a housekeeper, and remained with us until Mother

died a year later. After that she helped my Dad pack up the house, dispose

of many articles, and move up to a duplex on B Row. Raquel was offered a

retainer to look after the place in Dad's absence, but she refused, and

returned to La Serena where she had come from. I am convinced many years

later that she had done what Josefina had asked her to do, and had simply

gone home with her job done.

Raquel, My Mothers Maid, nurse and Companion at La Mina on the last day of operation of the Old Mine.

In early April, Bill Swayne came through town, and invited me to go on a

weekend trip to visit a prospect inland from Taltal with he and Blaine

Wiseman. I had a grand moment sitting casually on the seat in the back of

the new Geology pickup, waving to the kids at recess on Friday Morning as we

sped by. Revenge was Mrs Marsh's on Monday morning. We got back about 10PM

on the Sunday night after an exhausting trip, and of course I had paid no

attention to the dreaded Monday Morning Essay. There were a number of

caustic comments made that left me squirming in my seat, but unrepentant.

The next great expedition was a duck-hunting trip to La Ola. Dad had a

school chum, Melvin Williams who was the salesman for Joy Machinery in

Chile. Mel had come through Potrerillos on his annual trip, and they

proposed to go to La Ola at 2 Am on the Sunday. Our companions for the trip

were to be Ferd Liebenow, Blaine Wiseman, Carlos Riebeck and Len Holman. It

was late May, and bitterly cold. I rode out with Blaine Wiseman in the new

Geology Department Ford pickup. Mel was in his vehicle with a friend who was

a high officer in the Carabineros. Dad was in another vehicle with Len, and

Ferd and Carlos drove their sedans. We arrived at the small keeper's house

at the dam well before dawn. I can recall that the man stoked his potbelly

stove with a mixture of bunker oil and coal, and it was red hot. His dog

went out to the dam for an early morning swim, and had to break the ice to

get in! Tough dog. He had also put up a good number of ducks, as you could

hear the gackle of them as they flew off.

There was one less shotgun than party members, so that meant that boys did

without. I got the exalted job of driving up and down the creek trying to

put up the ducks so that they would fly past a number of corrugated blinds

that had been placed along the creek. There was a tremendous wind with a

temperature of about -20oC. The ducks stuck right on the water when they

flew, and they moved fast! I chased a number of flocks from the marsh down

to the dam, and then back up again. At one point, I chased a huge mob of

ducks in front of the blind where Ferd Libenow was shooting. I saw two ducks

fall on the other side of the creek, and stopped the truck to walk over and

pick them up. He surprised me by stepping out with one hip wader on and

plunging into the creek to get to the ducks ahead of me. He must have noted

my open mouth, and shouted to me to not worry, one leg was wood!

When the hunt was over in the early afternoon, I rode back with Ferd, and

listened to his stories of life in Bolivia and Chile in the 1920 and 30's.

He originally came from the Yaak River valley in Montana, and treated me as

an equal. I wish I could remember even a fraction of his stories today. I

used the plot of one of these stories for one of Mrs. Marsh’s dreaded Monday

Mourning essays a few weeks later. I got an "F" along with a curt note not

to listen to Mr. Libenow's stories!

Mother recovered sufficiently to come back to Potrerillos in May. Alfred was

due to come home for a school vacation in June, and she was really trying to

get herself together for this. She was partly paralyzed in the left side,

and had no feeling in her left hand. She threw herself into a frenzy of

sewing, and was able to turn out her usual good work. When Alfred came, she

went to Antofagasta to meet him. He was certainly shocked, since he had only

been told that she had been "unwell".

Alfred and I had a great social time together. There was a lively young

crowd, and dancing was the in thing. I had to attend school, and completed

the first half of Grade 8. It was decided that I was to return to Ohio with

Alfred and enter the Ninth Grade at the Ohio Military Institute. (My Mother

wrote home to her Mother that her babies had been taken away from her.)

We also went out with Dad and climbed Cerro Hueso behind the mine, which was

17,500 feet. This was a real hard all day climb but very satisfying. This

was my new altitude record. I later climbed both Vicuna and Dona Inez.

The mid-year school break signaled the end of my schooling at Potrerillos,

and I attained the brevet rank of teenager. There was a great bunch of kids

there, and I will try and list as many as I can remember. The Love girls,

Sue and Pat, Nona Couse, Betty Vetersneck, Donna Johnson, Joan Novak. My

photos were all lost in a house fire in 1990. We partied, visited each

other’s houses, danced, partied some more, went to all of the social

functions at the Andes Club, and drank all of the table wine we could get

our hands on. There was a passable band at the Club (Eddy y sus Muchachos)

that played real good dance music. Expeditions were mounted to the “Otro

Lado” to visit the Teatro Andes and freeze to death. Other trips were made

to Agua Dulce for picnics and the like.

My departure from Potrerillos was on August 12, 1956, having not quite spent

a year there. I should have stayed and finished Grade 8, but I was being

hustled out of the house so that I did not have to watch my Mother die. It

was obvious that there was a lot wrong by this time.

What did I get out of Potrerillos? The answer is a lot. I learned about the

unconditional love that people put out to you when you live in a proper

community. I learned that poor people with almost no education could have

wisdom, pride and politeness in a measure beyond that of well to do people

with education. I also learned that adults can and do spend a lot of time on

younger people trying to make them into something. I thought that the best

men that I knew were engineers, and decided to become one of them. Mrs.

Marsh taught me how to write, and made me learn the rules of grammar, which

are still in there somewhere.

I retuned to Potrerillos many times over the next 7 years, but was never to

live there again. My Mother passed away there on April 21, 1957, and that

made living in El Salvador for summer vacations a better thought. We went

over to Potrerillos for parties, but the old flavor was not there. Her death

seemed to have changed much for me, but the fine and warm people were still

the same.

In nearly 50 years not a day has passed that I do not think of that first

year in Potrerillos and its people. Man cannot make the clock of life run

backwards, but if I could, I would return it to September 1, 1955. I had

hoped to be at Barquito on September 1, 2005 with my half brother Paul to

celebrate a defining point in my family’s history. Unfortunately, business

pressure has made the trip impossible.

Frank Trask

August 11, 2005

Frank Trask, III

11 East Campbell Street

Kalgoorlie, Western Australia 6430

ftrask@bigpond.net.au